The Project Gutenberg EBook of Leonardo da Vinci, by Maurice W. Brockwell Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: Leonardo da Vinci Author: Maurice W. Brockwell Release Date: March, 2005 [EBook #7785] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on May 16, 2003] Edition: 10 Language: English Character set encoding: iso-8859-1 *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LEONARDO DA VINCI *** Produced by Juliet Sutherland, David Widger and the DP Team

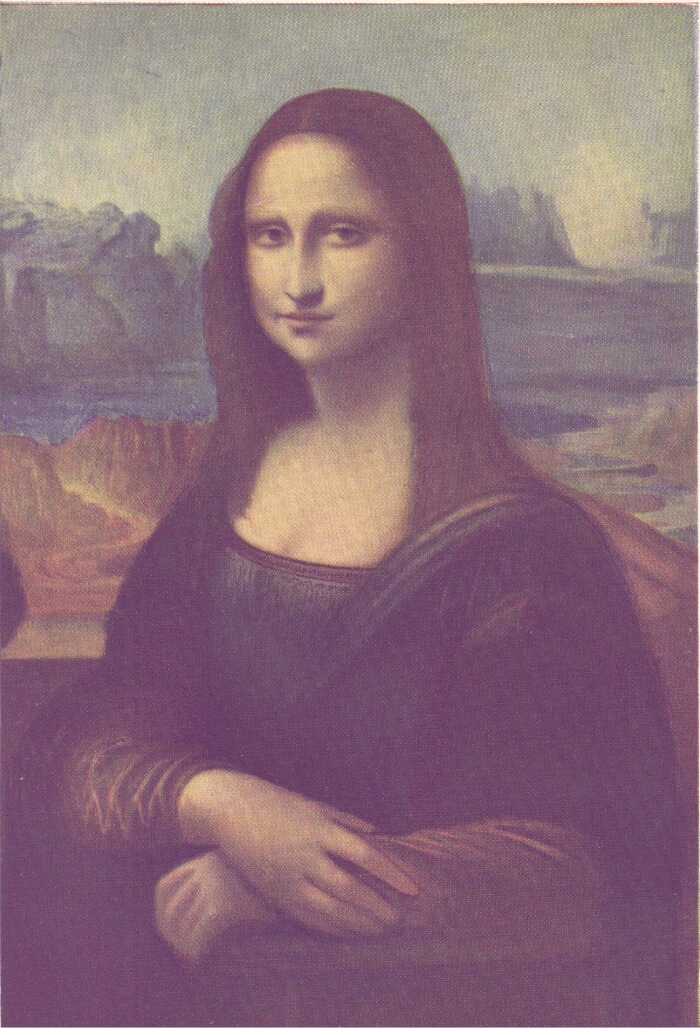

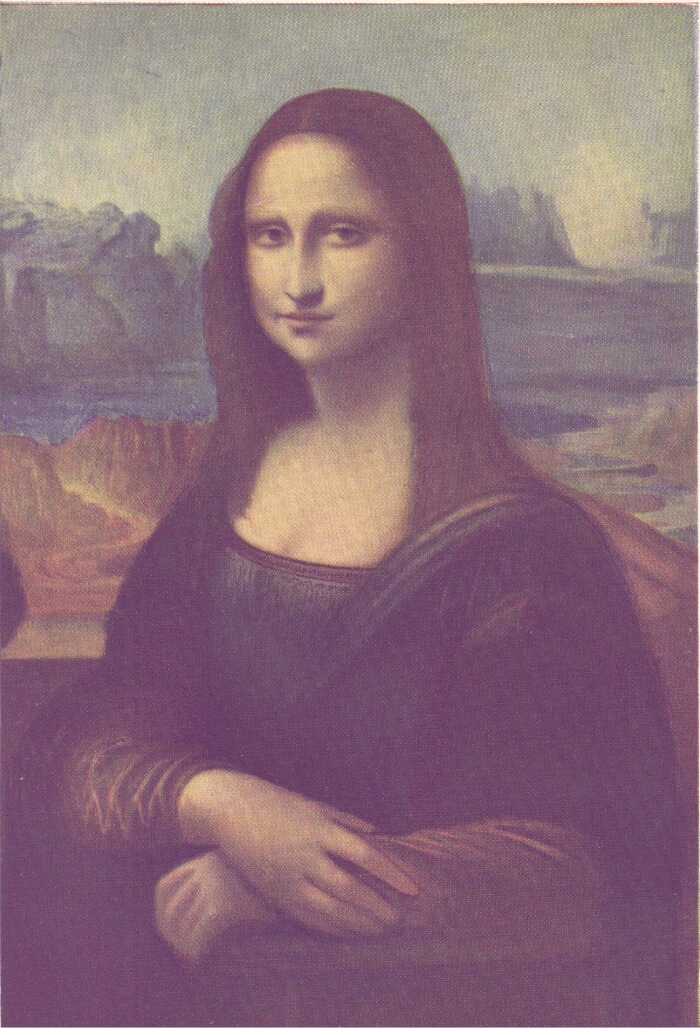

[Plate 1—MONA LISA. In the Louvre.

No. 1601. 2 ft 6 ½ ins. By 1 ft. 9 ins.(0.77 x 0.53)]

"Leonardo," wrote an English critic as far back as 1721, "was

a Man

so happy in his genius, so consummate in his Profession, so

accomplished in the Arts, so knowing in the Sciences, and withal,

so

much esteemed by the Age wherein he lived, his Works so

highly

applauded by the Ages which have succeeded, and his Name and

Memory

still preserved with so much Veneration by the present Age—that,

if

anything could equal the Merit of the Man, it must be the Success

he

met with. Moreover, 'tis not in Painting alone, but in

Philosophy,

too, that Leonardo surpassed all his Brethren of the

'Pencil.'"

This admirable summary of the great Florentine painter's

life's work

still holds good to-day.

His Birth

His Early Training

His Early Works

First Visit to Milan

In the East

Back in Milan

The Virgin of the Rocks

The Last Supper

The Court of Milan

Leonardo Leaves Milan

Mona Lisa

Battle of Anghiari

Again in Milan

In Rome

In France

His Death

His Art

His Mind

His Maxims

His Spell

His Descendants

Plate

I. Mona Lisa

In the Louvre

II. Annunciation

In the Uffizi Gallery, Florence

III. Virgin of the Rocks

In the National Gallery, London

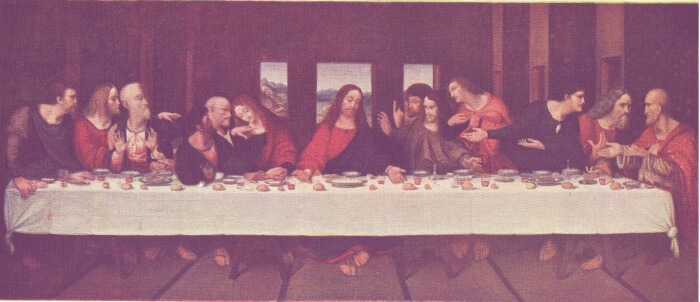

IV. The Last Supper

In the Refectory of Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan

V. Copy of the Last Supper

In the Diploma Gallery, Burlington House

VI. Head of Christ

In the Brera Gallery, Milan

VII. Portrait (presumed) of Lucrezia Crivelli

In the Louvre

VIII. Madonna, Infant Christ, and St Anne.

In the Louvre

Leonardo Da Vinci, the many-sided genius of the Italian

Renaissance,

was born, as his name implies, at the little town of Vinci, which

is

about six miles from Empoli and twenty miles west of Florence.

Vinci

is still very inaccessible, and the only means of conveyance is

the

cart of a general carrier and postman, who sets out on his

journey

from Empoli at sunrise and sunset. Outside a house in the middle

of

the main street of Vinci to-day a modern and white-washed bust of

the

great artist is pointed to with much pride by the

inhabitants.

Leonardo's traditional birthplace on the outskirts of the town

still

exists, and serves now as the headquarters of a farmer and small

wine

exporter.

Leonardo di Ser Piero d'Antonio di Ser Piero di Ser Guido

da

Vinci—for that was his full legal name—was the natural and

first-born son of Ser Piero, a country notary, who, like his

father,

grandfather, and great-grandfather, followed that honourable

vocation with distinction and success, and who

subsequently—when

Leonardo was a youth—was appointed notary to the Signoria of

Florence. Leonardo's mother was one Caterina, who afterwards

married

Accabriga di Piero del Vaccha of Vinci.

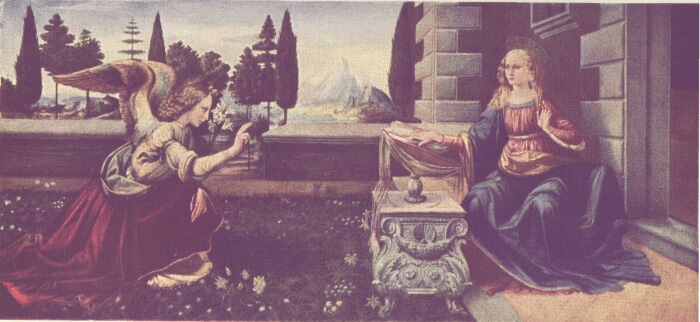

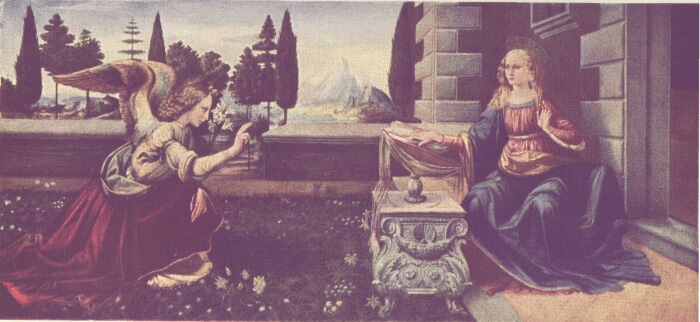

Plate II.—Annunciation In the Uffizi Gallery, Florence. No. 1288. 3 ft 3 ins. By 6 ft 11 ins. (0.99 x 2.18)] Although this panel is included in the Uffizi Catalogue as being by Leonardo, it is in all probability by his master, Verrocchio.]

The date of Leonardo's birth is not known with any certainty.

His age

is given as five in a taxation return made in 1457 by his

grandfather

Antonio, in whose house he was educated; it is therefore

concluded

that he was born in 1452. Leonardo's father Ser Piero, who

afterwards

married four times, had eleven children by his third and fourth

wives.

Is it unreasonable to suggest that Leonardo may have had these

numbers

in mind in 1496-1498 when he was painting in his famous "Last

Supper"

the figures of eleven Apostles and one outcast?

However, Ser Piero seems to have legitimised his "love child"

who very

early showed promise of extraordinary talent and untiring

energy.

Practically nothing is known about Leonardo's boyhood, but

Vasari

informs us that Ser Piero, impressed with the remarkable

character of

his son's genius, took some of his drawings to Andrea del

Verrocchio,

an intimate friend, and begged him earnestly to express an

opinion on

them. Verrocchio was so astonished at the power they revealed

that he

advised Ser Piero to send Leonardo to study under him. Leonardo

thus

entered the studio of Andrea del Verrocchio about 1469-1470. In

the

workshop of that great Florentine sculptor, goldsmith, and artist

he

met other craftsmen, metal workers, and youthful painters, among

whom

was Botticelli, at that moment of his development a jovial

_habitué_ of the Poetical Supper Club, who had not yet

given any

premonitions of becoming the poet, mystic, and visionary of

later

times. There also Leonardo came into contact with that

unoriginal

painter Lorenzo di Credi, his junior by seven years. He also,

no

doubt, met Perugino, whom Michelangelo called "that blockhead in

art."

The genius and versatility of the Vincian painter was, however,

in no

way dulled by intercourse with lesser artists than himself; on

the

contrary he vied with each in turn, and readily outstripped his

fellow

pupils. In 1472, at the age of twenty, he was admitted into the

Guild

of Florentine Painters.

Unfortunately very few of Leonardo's paintings have come down

to us.

Indeed there do not exist a sufficient number of finished and

absolutely authentic oil pictures from his own hand to afford

illustrations for this short chronological sketch of his life's

work.

The few that do remain, however, are of so exquisite a

quality—or

were until they were "comforted" by the uninspired restorer—that

we

can unreservedly accept the enthusiastic records of tradition

in

respect of all his works. To rightly understand the essential

characteristics of Leonardo's achievements it is necessary to

regard him as a scientist quite as much as an artist, as a

philosopher

no less than a painter, and as a draughtsman rather than a

colourist.

There is hardly a branch of human learning to which he did not

at

one time or another give his eager attention, and he was

engrossed in

turn by the study of architecture—the foundation-stone of all

true

art—sculpture, mathematics, engineering and music. His

versatility

was unbounded, and we are apt to regret that this many-sided

genius

did not realise that it is by developing his power within

certain

limits that the great master is revealed. Leonardo may be

described as

the most Universal Genius of Christian times-perhaps of all

time.

[PLATE III. THE VIRGIN OF THE ROCKS In the National Gallery. No. 1093. 6 ft. ½ in. h. by 3 ft 9 ½ in. w. (1.83 x 1.15)] This picture was painted in Milan about 1495 by Ambrogio da Predis under the supervision and guidance of Leonardo da Vinci, the essential features of the composition being borrowed from the earlier "Vierge aux Rochers," now in the Louvre.]

[Plate II.—Annunciation In the Uffizi Gallery, Florence. No. 1288. 3 ft 3 ins. By 6 ft 11 ins. (0.99 x 2.18)]

To about the year 1472 belongs the small picture of the

"Annunciation," now in the Louvre, which after being the subject

of

much contention among European critics has gradually won its way

to

general recognition as an early work by Leonardo himself. That it

was

painted in the studio of Verrocchio was always admitted, but it

was

long catalogued by the Louvre authorities under the name of

Lorenzo di

Credi. It is now, however, attributed to Leonardo (No. 1602 A).

Such

uncertainties as to attribution were common half a century ago

when

scientific art criticism was in its infancy.

Another painting of the "Annunciation," which is now in the

Uffizi

Gallery (No. 1288) is still officially attributed to Leonardo.

This

small picture, which has been considerably repainted, and is

perhaps

by Andrea del Verrocchio, Leonardo's master, is the subject of

Plate

II.

To January 1473 belongs Leonardo's earliest dated work, a

pen-and-ink

drawing—"A Wide View over a Plain," now in the Uffizi. The

inscription together with the date in the top left-hand corner

is

reversed, and proves a remarkable characteristic of

Leonardo's

handwriting—viz., that he wrote from right to left; indeed, it

has

been suggested that he did this in order to make it difficult for

any

one else to read the words, which were frequently committed to

paper

by the aid of peculiar abbreviations.

Leonardo continued to work in his master's studio till about

1477. On

January 1st of the following year, 1478, he was commissioned to

paint

an altar-piece for the Chapel of St. Bernardo in the Palazzo

Vecchio,

and he was paid twenty-five florins on account. He, however,

never

carried out the work, and after waiting five years the

Signoria

transferred the commission to Domenico Ghirlandajo, who also

failed to

accomplish the task, which was ultimately, some seven years

later,

completed by Filippino Lippi. This panel of the "Madonna

Enthroned,

St. Victor, St. John Baptist, St. Bernard, and St. Zenobius,"

which is

dated February 20, 1485, is now in the Uffizi.

That Leonardo was by this time a facile draughtsman is

evidenced by

his vigorous pen-and-ink sketch—now in a private collection

in

Paris—of Bernardo Bandini, who in the Pazzi Conspiracy of April

1478

stabbed Giuliano de' Medici to death in the Cathedral at

Florence

during High Mass. The drawing is dated December 29, 1479, the

date of

Bandini's public execution in Florence.

In that year also, no doubt, was painted the early and, as

might be

expected, unfinished "St. Jerome in the Desert," now in the

Vatican, the

under-painting being in umber and _terraverte_. Its authenticity

is

vouched for not only by the internal evidence of the picture

itself, but

also by the similarity of treatment seen in a drawing in the

Royal

Library at Windsor. Cardinal Fesch, a princely collector in Rome

in the

early part of the nineteenth century, found part of the

picture—the

torso—being used as a box-cover in a shop in Rome. He long

afterwards

discovered in a shoemaker's shop a panel of the head which

belonged to

the torso. The jointed panel was eventually purchased by Pope

Pius IX.,

and added to the Vatican Collection.

In March 1480 Leonardo was commissioned to paint an

altar-piece for

the monks of St. Donato at Scopeto, for which payment in advance

was

made to him. That he intended to carry out this contract seems

most

probable. He, however, never completed the picture, although it

gave

rise to the supremely beautiful cartoon of the "Adoration of

the

Magi," now in the Uffizi (No. 1252). As a matter of course it

is

unfinished, only the under-painting and the colouring of the

figures

in green on a brown ground having been executed. The rhythm of

line,

the variety of attitude, the profound feeling for landscape and

an

early application of chiaroscuro effect combine to render this

one of

his most characteristic productions.

Vasari tells us that while Verrocchio was painting the

"Baptism of

Christ" he allowed Leonardo to paint in one of the attendant

angels

holding some vestments. This the pupil did so admirably that

his

remarkable genius clearly revealed itself, the angel which

Leonardo

painted being much better than the portion executed by his

master.

This "Baptism of Christ," which is now in the Accademia in

Florence

and is in a bad state of preservation, appears to have been a

comparatively early work by Verrocchio, and to have been

painted

in 1480-1482, when Leonardo would be about thirty years of

age.

To about this period belongs the superb drawing of the

"Warrior," now

in the Malcolm Collection in the British Museum. This drawing may

have

been made while Leonardo still frequented the studio of Andrea

del

Verrocchio, who in 1479 was commissioned to execute the

equestrian

statue of Bartolommeo Colleoni, which was completed twenty years

later

and still adorns the Campo di San Giovanni e Paolo in Venice.

About 1482 Leonardo entered the service of Ludovico Sforza,

having

first written to his future patron a full statement of his

various

abilities in the following terms:—

"Having, most illustrious lord, seen and pondered over the

experiments

made by those who pass as masters in the art of inventing

instruments

of war, and having satisfied myself that they in no way differ

from

those in general use, I make so bold as to solicit, without

prejudice

to any one, an opportunity of informing your excellency of some

of my

own secrets."

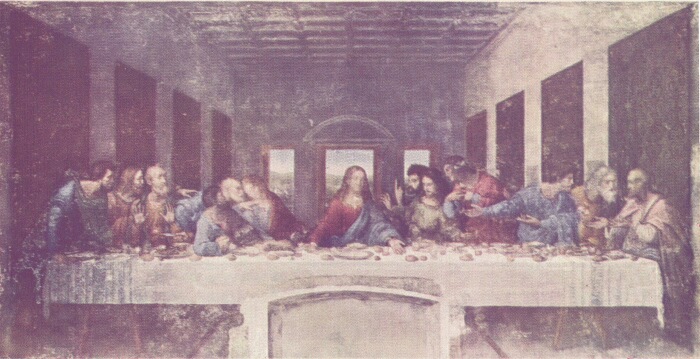

[PLATE IV.-THE LAST SUPPER Refectory of St. Maria delle Grazie, Milan. About 13 feet 8 ins. h. by 26 ft. 7 ins. w. (4.16 x 8.09)]

He goes on to say that he can construct light bridges which

can be

transported, that he can make pontoons and scaling ladders, that

he

can construct cannon and mortars unlike those commonly used, as

well

as catapults and other engines of war; or if the fight should

take

place at sea that he can build engines which shall be suitable

alike

for defence as for attack, while in time of peace he can erect

public

and private buildings. Moreover, he urges that he can also

execute

sculpture in marble, bronze, or clay, and, with regard to

painting,

"can do as well as any one else, no matter who he may be." In

conclusion, he offers to execute the proposed bronze equestrian

statue

of Francesco Sforza "which shall bring glory and never-ending

honour

to that illustrious house."

It was about 1482, the probable date of Leonardo's migration

from

Florence to Milan, that he painted the "Vierge aux Rochers," now

in

the Louvre (No. 1599). It is an essentially Florentine picture,

and

although it has no pedigree earlier than 1625, when it was in

the

Royal Collection at Fontainebleau, it is undoubtedly much earlier

and

considerably more authentic than the "Virgin of the Rocks," now

in the

National Gallery (Plate III.).

He certainly set to work about this time on the projected

statue of

Francesco Sforza, but probably then made very little progress

with it.

He may also in that year or the next have painted the lost

portrait of

Cecilia Gallerani, one of the mistresses of Ludovico Sforza. It

has,

however, been surmised that that lady's features are preserved to

us

in the "Lady with a Weasel," by Leonardo's pupil Boltraffio,

which is

now in the Czartoryski Collection at Cracow.

The absence of any record of Leonardo in Milan, or elsewhere

in Italy,

between 1483 and 1487 has led critics to the conclusion, based

on

documentary evidence of a somewhat complicated nature, that he

spent

those years in the service of the Sultan of Egypt, travelling

in

Armenia and the East as his engineer.

In 1487 he was again resident in Milan as general

artificer—using

that term in its widest sense—to Ludovico. Among his various

activities at this period must be mentioned the designs he made

for

the cupola of the cathedral at Milan, and the scenery he

constructed

for "Il Paradiso," which was written by Bernardo Bellincioni on

the

occasion of the marriage of Gian Galeazzo with Isabella of

Aragon.

About 1489-1490 he began his celebrated "Treatise on Painting"

and

recommenced work on the colossal equestrian statue of

Francesco

Sforza, which was doubtless the greatest of all his achievements

as a

sculptor. It was, however, never cast in bronze, and was

ruthlessly

destroyed by the French bowmen in April 1500, on their occupation

of

Milan after the defeat of Ludovico at the battle of Novara. This

is

all the more regrettable as no single authentic piece of

sculpture

has come down to us from Leonardo's hand, and we can only judge

of his

power in this direction from his drawings, and the

enthusiastic

praise of his contemporaries.

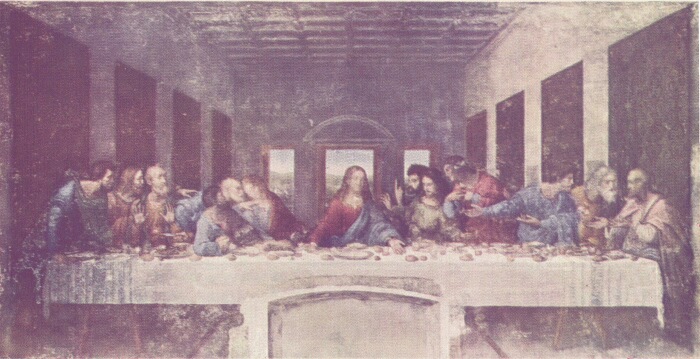

This copy is usually ascribed to Marco d'Oggiono, but some

critics

claim that it is by Gianpetrino. It is the same size as the

original.]

The "Virgin of the Rocks" (Plate III.), now in the National

Gallery,

corresponds exactly with a painting by Leonardo which was

described by

Lomazzo about 1584 as being in the Chapel of the Conception in

the

Church of St. Francesco at Milan. This picture, the only

_oeuvre_

in this gallery with which Leonardo's name can be connected,

was

brought to England in 1777 by Gavin Hamilton, and sold by him to

the

Marquess of Lansdowne, who subsequently exchanged it for

another

picture in the Collection of the Earl of Suffolk at Charlton

Park,

Wiltshire, from whom it was eventually purchased by the

National

Gallery for £9000. Signor Emilio Motta, some fifteen years

ago,

unearthed in the State Archives of Milan a letter or memorial

from

Giovanni Ambrogio da Predis and Leonardo da Vinci to the Duke

of

Milan, praying him to intervene in a dispute, which had arisen

between

the petitioners and the Brotherhood of the Conception, with

regard to

the valuation of certain works of art furnished for the chapel of

the

Brotherhood in the church of St. Francesco. The only logical

deduction

which can be drawn from documentary evidence is that the "Vierge

aux

Rochers" in the Louvre is the picture, painted about 1482,

which

between 1491 and 1494 gave rise to the dispute, and that, when it

was

ultimately sold by the artists for the full price asked to

some

unknown buyer, the National Gallery version was executed for

a

smaller price mainly by Ambrogio da Predisunder the supervision,

and

with the help, of Leonardo to be placed in the Chapel of the

Conception.

The differences between the earlier, the more authentic, and

the more

characteristically Florentine "Vierge aux Rochers," in the

Louvre, and

the "Virgin of the Rocks," in the National Gallery, are that in

the

latter picture the hand of the angel, seated by the side of the

Infant

Christ, is raised and pointed in the direction of the little St.

John

the Baptist; that the St John has a reed cross and the three

principal

figures have gilt nimbi, which were, however, evidently added

much

later. In the National Gallery version the left hand of the

Madonna,

the Christ's right hand and arm, and the forehead of St. John

the

Baptist are freely restored, while a strip of the foreground

right

across the whole picture is ill painted and lacks accent. The

head of

the angel is, however, magnificently painted, and by Leonardo;

the

panel, taken as a whole, is exceedingly beautiful and full of

charm

and tenderness.

Between 1496 and 1498 Leonardo painted his _chef d'oeuvre_,

the

"Last Supper," (Plate IV.) for the end wall of the Refectory of

the

Dominican Convent of S. Maria delle Grazie at Milan. It was

originally

executed in tempera on a badly prepared stucco ground and began

to

deteriorate a very few years after its completion. As early as

1556 it

was half ruined. In 1652 the monks cut away a part of the

fresco

including the feet of the Christ to make a doorway. In 1726

one

Michelangelo Belotti, an obscure Milanese painter, received

£300 for

the worthless labour he bestowed on restoring it. He seems to

have

employed some astringent restorative which revived the

colours

temporarily, and then left them in deeper eclipse than before. In

1770

the fresco was again restored by Mazza. In 1796 Napoleon's

cavalry,

contrary to his express orders, turned the refectory into a

stable,

and pelted the heads of the figures with dirt. Subsequently

the

refectory was used to store hay, and at one time or another it

has

been flooded. In 1820 the fresco was again restored, and in 1854

this

restoration was effaced. In October 1908 Professor Cavenaghi

completed

the delicate task of again restoring it, and has, in the opinion

of

experts, now preserved it from further injury. In addition,

the

devices of Ludovico and his Duchess and a considerable amount

of

floral decoration by Leonardo himself have been brought to

light.

Leonardo has succeeded in producing the effect of the _coup

de

théâtre_ at the moment when Jesus said "One of you

shall betray

me." Instantly the various apostles realise that there is a

traitor

among their number, and show by their different gestures

their

different passions, and reveal their different temperaments. On

the

left of Christ is St. John who is overcome with grief and is

interrogated by the impetuous Peter, near whom is seated

Judas

Iscariot who, while affecting the calm of innocence, is quite

unable

to conceal his inner feelings; he instinctively clasps the

money-bag

and in so doing upsets the salt-cellar.

It will be remembered that the Prior of the Convent complained

to

Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan, that Leonardo was taking too long

to

paint the fresco and was causing the Convent considerable

inconvenience. Leonardo had his revenge by threatening to paint

the

features of the impatient Prior into the face of Judas Iscariot.

The

incident has been quaintly told in the following lines:—

"Padre Bandelli, then, complains of me

Because, forsooth, I have not drawn a line

Upon the Saviour's head; perhaps, then, he

Could without trouble paint that head divine.

But think, oh Signor Duca, what should be

The pure perfection of Our Saviour's face—

What sorrowing majesty, what noble grace,

At that dread moment when He brake the bread,

And those submissive words of pathos said:

"'By one among you I shall be betrayed,'—

And say if 'tis an easy task to find

Even among the best that walk this Earth,

The fitting type of that divinest worth,

That has its image solely in the mind.

Vainly my pencil struggles to express

The sorrowing grandeur of such holiness.

In patient thought, in ever-seeking prayer,

I strive to shape that glorious face within,

But the soul's mirror, dulled and dimmed by sin,

Reflects not yet the perfect image there.

Can the hand do before the soul has wrought;

Is not our art the servant of our thought?

"And Judas too, the basest face I see,

Will not contain his utter infamy;

Among the dregs and offal of mankind

Vainly I seek an utter wretch to find.

He who for thirty silver coins could sell

His Lord, must be the Devil's miracle.

Padre Bandelli thinks it easy is

To find the type of him who with a kiss

Betrayed his Lord. Well, what I can I'll do;

And if it please his reverence and you,

For Judas' face I'm willing to paint his."

* * * * *

"... I dare not paint

Till all is ordered and matured within,

Hand-work and head-work have an earthly taint,

But when the soul commands I shall begin;

On themes like these I should not dare to dwell

With our good Prior—they to him would be

Mere nonsense; he must touch and taste and see,

And facts, he says, are never mystical."

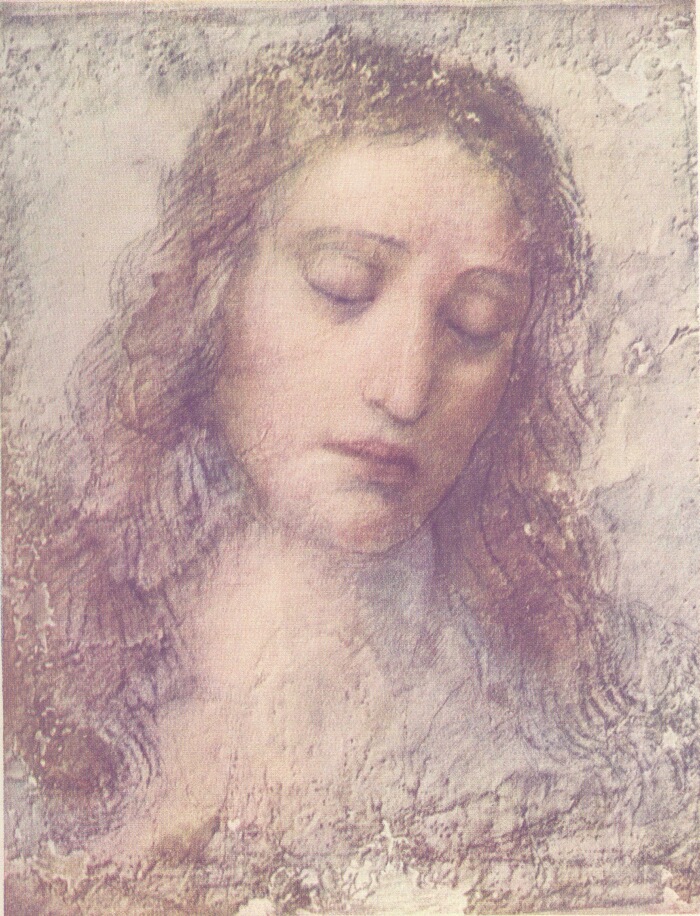

[PLATE VI.—THE HEAD OF CHRIST In the Brera Gallery, Milan. No. 280. 1 ft. 0-1/2 ins. by 1 ft. 4 ins. (0.32 x 0.40)]

The copy of the "Last Supper" (Plate V.) by Marco d'Oggiono,

now in

the Diploma Gallery at Burlington House, was made shortly after

the

original painting was completed. It gives but a faint echo of

that

sublime work "in which the ideal and the real were blended in

perfect

unity." This copy was long in the possession of the Carthusians

in

their Convent at Pavia, and, on the suppression of that Order

and

the sale of their effects in 1793, passed into the possession of

a

grocer at Milan. It was subsequently purchased for £600 by

the Royal

Academy on the advice of Sir Thomas Lawrence, who left no

stone

unturned to acquire also the original studies for the heads of

the

Apostles. Some of these in red and black chalk are now

preserved

in the Royal Library at Windsor, where there are in all 145

drawings

by Leonardo.

Several other old copies of the fresco exist, notably the one

in the

Louvre. Francis I. wished to remove the whole wall of the

Refectory to

Paris, but he was persuaded that that would be impossible;

the

Constable de Montmorency then had a copy made for the Chapel of

the

Château d'Ecouen, whence it ultimately passed to the

Louvre.

The singularly beautiful "Head of Christ" (Plate VI.), now in

the

Brera Gallery at Milan, is the original study for the head of

the

principal figure in the fresco painting of the "Last Supper."

In

spite of decay and restoration it expresses "the most

elevated

seriousness together with Divine Gentleness, pain on account

of

the faithlessness of His disciples, a full presentiment of His

own

death, and resignation to the will of His Father."

Ludovico, to whom Leonardo was now court-painter, had married

Beatrice

d'Este, in 1491, when she was only fifteen years of age. The

young

Duchess, who at one time owned as many as eighty-four splendid

gowns,

refused to wear a certain dress of woven gold, which her husband

had

given her, if Cecilia Gallerani, the Sappho of her day, continued

to

wear a very similar one, which presumably had been given to her

by

Ludovico. Having discarded Cecilia, who, as her tastes did not

lie in

the direction of the Convent, was married in 1491 to Count

Ludovico

Bergamini, the Duke in 1496 became enamoured of Lucrezia

Crivelli, a

lady-in-waiting to the Duchess Beatrice.

Leonardo, as court painter, perhaps painted a portrait, now

lost, of

Lucrezia, whose features are more likely to be preserved to us in

the

portrait by Ambrogio da Predis, now in the Collection of the Earl

of

Roden, than in the quite unauthenticated portrait (Plate VII.),

now in

the Louvre (No. 1600).

On January 2, 1497, Beatrice spent three hours in prayer in

the church

of St. Maria delle Grazie, and the same night gave birth to a

stillborn child. In a few hours she passed away, and from that

moment

Ludovico was a changed man. He went daily to see her tomb, and

was

quite overcome with grief.

In April 1498, Isabella d'Este, Beatrice's elder, more

beautiful, and

more graceful sister, "at the sound of whose name all the muses

rise

and do reverence" wrote to Cecilia Gallerani, or Bergamini,

asking her

to lend her the portrait which Leonardo had painted of her

some

fifteen years earlier, as she wished to compare it with a picture

by

Giovanni Bellini. Cecilia graciously lent the picture—now

presumably

lost—adding her regret that it no longer resembled her.

Among the last of Leonardo da Vinci's works in Milan towards

the end

of 1499 was, probably, the superb cartoon of "The Virgin and

Child

with St. Anne and St. John," now at Burlington House. Though

little

known to the general public, this large drawing on _carton_,

or

stiff paper, is one of the greatest of London's treasures, as

it

reveals the sweeping line of Leonardo's powerful draughtsmanship.

It

was in the Pompeo Leoni, Arconati, Casnedi, and Udney

Collections

before passing to the Royal Academy.

In 1499 the stormy times in Milan foreboded the end of

Ludovico's

reign. In April of that year we read of his giving a vineyard

to

Leonardo; in September Ludovico had to leave Milan for the Tyrol

to

raise an army, and on the 14th of the same month the city was

sold by

Bernardino di Corte to the French, who occupied it from 1500 to

1512.

Ludovico may well have had in mind the figure of the traitor in

the

"Last Supper" when he declared that "Since the days of Judas

Iscariot

there has never been so black a traitor as Bernardino di Corte."

On

October 6th Louis XII. entered the city. Before the end of the

year

Leonardo, realising the necessity for his speedy departure, sent

six

hundred gold florins by letter of exchange to Florence to be

placed

to his credit with the hospital of S. Maria Nuova.

In the following year, Ludovico having been defeated at

Novara,

Leonardo was a homeless wanderer. He left Milan for Mantua, where

he

drew a portrait in chalk of Isabella d'Este, which is now in

the

Louvre. Leonardo eventually arrived in Florence about Easter

1500.

After apparently working there in 1501 on a second Cartoon,

similar in

most respects to the one he had executed in Milan two years

earlier,

he travelled in Umbria, visiting Orvieto, Pesaro, Rimini, and

other

towns, acting as engineer and architect to Cesare Borgia, for

whom he

planned a navigable canal between Cesena and Porto

Cese-natico.

[PLATE VII.-PORTRAIT (PRESUMED) OF LUCREZIA CRIVELLI In the Louvre. No. 1600 [483]. 2 ft by I ft 5 ins. (0.62 x 0.44) This picture, although officially attributed to Leonardo, is probably not by him, and almost certainly does not represent Lucrezia Crivelli. It was once known as a "Portrait of a Lady" and is still occasionally miscalled "La Belle Féronnière."]

Early in 1503 he was back again in Florence, and set to work

in

earnest on the "Portrait of Mona Lisa" (Plate I.), now in the

Louvre

(No. 1601). Lisa di Anton Maria di Noldo Gherardini was the

daughter

of Antonio Gherardini. In 1495 she married Francesco di

Bartolommeo de

Zenobi del Giocondo. It is from the surname of her husband that

she

derives the name of "La Joconde," by which her portrait is

officially

known in the Louvre. Vasari is probably inaccurate in saying

that

Leonardo "loitered over it for four years, and finally left

it

unfinished." He may have begun it in the spring of 1501 and,

probably

owing to having taken service under Cesare Borgia in the

following

year, put it on one side, ultimately completing it after working

on

the "Battle of Anghiari" in 1504. Vasari's eulogy of this

portrait may

with advantage be quoted: "Whoever shall desire to see how far

art can

imitate nature may do so to perfection in this head, wherein

every

peculiarity that could be depicted by the utmost subtlety of

the

pencil has been faithfully reproduced. The eyes have the

lustrous

brightness and moisture which is seen in life, and around them

are

those pale, red, and slightly livid circles, also proper to

nature.

The nose, with its beautiful and delicately roseate nostrils,

might be

easily believed to be alive; the mouth, admirable in its outline,

has

the lips uniting the rose-tints of their colour with those of

the

face, in the utmost perfection, and the carnation of the cheek

does

not appear to be painted, but truly flesh and blood. He who

looks

earnestly at the pit of the throat cannot but believe that he

sees the

beating of the pulses. Mona Lisa was exceedingly beautiful, and

while

Leonardo was painting her portrait, he took the precaution of

keeping

some one constantly near her to sing or play on instruments, or

to

jest and otherwise amuse her."

Leonardo painted this picture in the full maturity of his

talent, and,

although it is now little more than a monochrome owing to the

free and

merciless restoration to which it has been at times subjected, it

must

have created a wonderful impression on those who saw it in the

early

years of the sixteenth century. It is difficult for the

unpractised

eye to-day to form any idea of its original beauty. Leonardo has

here

painted this worldly-minded woman—her portrait is much more

famous

than she herself ever was—with a marvellous charm and suavity,

a

finesse of expression never reached before and hardly ever

equalled

since. Contrast the head of the Christ at Milan, Leonardo's

conception

of divinity expressed in perfect humanity, with the subtle

and

sphinx-like smile of this languorous creature.

The landscape background, against which Mona Lisa is posed,

recalls

the severe, rather than exuberant, landscape and the dim vistas

of

mountain ranges seen in the neighbourhood of his own birthplace.

The

portrait was bought during the reign of Francis I. for a sum

which is

to-day equal to about £1800. Leonardo, by the way, does not

seem to

have been really affected by any individual affection for any

woman,

and, like Michelangelo and Raphael, never married.

In January 4, 1504, Leonardo was one of the members of the

Committee

of Artists summoned to advise the Signoria as to the most

suitable

site for the erection of Michelangelo's statue of "David," which

had

recently been completed.

In the following May he was commissioned by the Signoria to

decorate

one of the walls of the Council Hall of the Palazzo Vecchio.

The

subject he selected was the "Battle of Anghiari." Although he

completed the cartoon, the only part of the composition which

he

eventually executed in colour was an incident in the

foreground

which dealt with the "Battle of the Standard." One of the

many

supposed copies of a study of this mural painting now hangs on

the

south-east staircase in the Victoria and Albert Museum. It

depicts the

Florentines under Cardinal Ludovico Mezzarota Scarampo

fighting

against the Milanese under Niccolò Piccinino, the General

of Filippo

Maria Visconti, on June 29, 1440.

Leonardo was back in Milan in May 1506 in the service of the

French

King, for whom he executed, apparently with the help of

assistants,

"the Madonna, the Infant Christ, and Saint Anne" (Plate VIII.).

The

composition of this oil-painting seems to have been built up on

the

second cartoon, which he had made some eight years earlier, and

which

was apparently taken to France in 1516 and ultimately lost.

From 1513-1515 he was in Rome, where Giovanni de' Medici had

been

elected Pope under the title of Leo X. He did not, however, work

for

the Pope, although he resided in the Vatican, his time being

occupied

in studying acoustics, anatomy, optics, geology, minerals,

engineering, and geometry!

At last in 1516, three years before his death, Leonardo left

his

native land for France, where he received from Francis I. a

princely

income. His powers, however, had already begun to fail, and

he

produced very little in the country of his adoption. It is,

nevertheless, only in the Louvre that his achievements as a

painter

can to-day be adequately studied.

[PLATE VIII.-MADONNA, INFANT CHRIST, AND ST. ANNE In the Louvre. No. 1508. 5 ft. 7 in. h. by 4 ft. 3 in. w. (1.70 x 1.29) Painted between 1509 and 1516 with the help of assistants.]

On October 10, 1516, when he was resident at the Manor House

of Cloux

near Amboise in Touraine with Francesco Melzi, his friend and

assistant, he showed three of his pictures to the Cardinal of

Aragon,

but his right hand was now paralysed, and he could "no longer

colour

with that sweetness with which he was wont, although still able

to

make drawings and to teach others."

It was no doubt in these closing years of his life that he

drew the

"Portrait of Himself" in red chalk, now at Turin, which is

probably

the only authentic portrait of him in existence.

On April 23, 1519—Easter Eve—exactly forty-five years before

the

birth of Shakespeare, Leonardo da Vinci made his will, and on May

2 of

the same year he passed away.

Vasari informs us that Leonardo, "having become old, lay sick

for many

months, and finding himself near death and being sustained in the

arms

of his servants and friends, devoutly received the Holy

Sacrament. He

was then seized with a paroxysm, the forerunner of death, when

King

Francis I., who was accustomed frequently and affectionately to

visit

him, rose and supported his head to give him such assistance and

to do

him such favour as he could in the hope of alleviating his

sufferings.

The spirit of Leonardo, which was most divine, conscious that he

could

attain to no greater honour, departed in the arms of the

monarch,

being at that time in the seventy-fifth year of his age." The

not

over-veracious chronicler, however, is here drawing largely upon

his

imagination. Leonardo was only sixty-seven years of age, and the

King

was in all probability on that date at St. Germain-en Laye!

Thus died "Mr. Lionard de Vincy, the noble Milanese,

painter,

engineer, and architect to the King, State Mechanician" and

"former

Professor of Painting to the Duke of Milan."

"May God Almighty grant him His eternal peace," wrote his

friend and

assistant Francesco Melzi. "Every one laments the loss of a man

whose

like Nature cannot produce a second time."

Leonardo, whose birth antedates that of Michelangelo and

Raphael by

twenty three and thirty-one years respectively, was thus in

the

forefront of the Florentine Renaissance, his life coinciding

almost

exactly with the best period of Tuscan painting.

Leonardo was the first to investigate scientifically and to

apply to

art the laws of light and shade, though the preliminary

investigations

of Piero della Francesca deserve to be recorded.

He observed with strict accuracy the subtleties of

chiaroscuro—light

and shade apart from colour; but, as one critic has pointed out,

his

gift of chiaroscuro cost the colour-life of many a noble

picture.

Leonardo was "a tonist, not a colourist," before whom the whole

book

of nature lay open.

It was not instability of character but versatility of mind

which

caused him to undertake many things that having commenced he

afterwards abandoned, and the probability is that as soon as he

saw

exactly how he could solve any difficulty which presented itself,

he

put on one side the merely perfunctory execution of such a

task.

In the Forster collection in the Victoria and Albert museum

three of

Leonardo's note-books with sketches are preserved, and it is

stated

that it was his practice to carry about with him, attached to

his

girdle, a little book for making sketches. They prove that he

was

left-handed and wrote from right to left.

We can readily believe the statements of Benvenuto Cellini,

the

sixteenth-century Goldsmith, that Francis I. "did not believe

that any other man had come into the world who had attained so

great a

knowledge as Leonardo, and that not only as sculptor, painter,

and

architect, for beyond that he was a profound philosopher." It

was

Cellini also who contended that "Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo,

and

Raphael are the Book of the World."

Leonardo anticipated many eminent scientists and inventors in

the

methods of investigation which they adopted to solve the many

problems

with which their names are coupled. Among these may be cited

Copernicus' theory of the earth's movement, Lamarck's

classification

of vertebrate and invertebrate animals, the laws of friction,

the laws of combustion and respiration, the elevation of the

continents, the laws of gravitation, the undulatory theory of

light

and heat, steam as a motive power in navigation, flying machines,

the

invention of the camera obscura, magnetic attraction, the use of

the

stone saw, the system of canalisation, breech loading cannon,

the

construction of fortifications, the circulation of the blood,

the

swimming belt, the wheelbarrow, the composition of explosives,

the

invention of paddle wheels, the smoke stack, the mincing machine!

It

is, therefore, easy to see why he called "Mechanics the

Paradise

of the Sciences."

Leonardo was a SUPERMAN.

The eye is the window of the soul.

Tears come from the heart and not from the brain.

The natural desire of good men is knowledge.

A beautiful body perishes, but a work of art dies not.

Every difficulty can be overcome by effort.

Time abides long enough for those who make use of it.

Miserable men, how often do you enslave yourselves

to gain money!

The influence of Leonardo was strongly felt in Milan, where he

spent

so many of the best years of his life and founded a School of

painting. He was a close observer of the gradation and reflex

of

light, and was capable of giving to his discoveries a practical

and

aesthetic form. His strong personal character and the fascination

of

his genius enthralled his followers, who were satisfied to repeat

his

types, to perpetuate the "grey-hound eye," and to make use of

his

little devices. Among this group of painters may be mentioned

Boltraffio, who perhaps painted the "Presumed Portrait of

Lucrezia

Crivelli" (Plate VII.), which is officially attributed in the

Louvre

to the great master himself.

Signor Uzielli has shown that one Tommaso da Vinci, a

descendant of

Domenico (one of Leonardo's brothers), was a few years ago a

peasant

at Bottinacio near Montespertoli, and had then in his possession

the

family papers, which now form part of the archives of the

Accademia

dei Lincei at Rome. It was proved also that Tommaso had given

his

eldest son "the glorious name of Leonardo."

End of Project Gutenberg's Leonardo da Vinci, by Maurice W. Brockwell

*** END OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LEONARDO DA VINCI ***

This file should be named 8ldvn10h.htm or 8ldvn10h.zip

Corrected EDITIONS of our eBooks get a new NUMBER, 8ldvn11h.htm

VERSIONS based on separate sources get new LETTER, 8ldvn10ah.htm

Produced by Juliet Sutherland, David Widger and the DP Team

Project Gutenberg eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the US

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we usually do not

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

We are now trying to release all our eBooks one year in advance

of the official release dates, leaving time for better editing.

Please be encouraged to tell us about any error or corrections,

even years after the official publication date.

Please note neither this listing nor its contents are final til

midnight of the last day of the month of any such announcement.

The official release date of all Project Gutenberg eBooks is at

Midnight, Central Time, of the last day of the stated month. A

preliminary version may often be posted for suggestion, comment

and editing by those who wish to do so.

Most people start at our Web sites at:

http://gutenberg.net or

http://promo.net/pg

These Web sites include award-winning information about Project

Gutenberg, including how to donate, how to help produce our new

eBooks, and how to subscribe to our email newsletter (free!).

Those of you who want to download any eBook before announcement

can get to them as follows, and just download by date. This is

also a good way to get them instantly upon announcement, as the

indexes our cataloguers produce obviously take a while after an

announcement goes out in the Project Gutenberg Newsletter.

http://www.ibiblio.org/gutenberg/etext03 or

ftp://ftp.ibiblio.org/pub/docs/books/gutenberg/etext03

Or /etext02, 01, 00, 99, 98, 97, 96, 95, 94, 93, 92, 92, 91 or 90

Just search by the first five letters of the filename you want,

as it appears in our Newsletters.

Information about Project Gutenberg (one page)

We produce about two million dollars for each hour we work. The

time it takes us, a rather conservative estimate, is fifty hours

to get any eBook selected, entered, proofread, edited, copyright

searched and analyzed, the copyright letters written, etc. Our

projected audience is one hundred million readers. If the value

per text is nominally estimated at one dollar then we produce $2

million dollars per hour in 2002 as we release over 100 new text

files per month: 1240 more eBooks in 2001 for a total of 4000+

We are already on our way to trying for 2000 more eBooks in 2002

If they reach just 1-2% of the world's population then the total

will reach over half a trillion eBooks given away by year's end.

The Goal of Project Gutenberg is to Give Away 1 Trillion eBooks!

This is ten thousand titles each to one hundred million readers,

which is only about 4% of the present number of computer users.

Here is the briefest record of our progress (* means estimated):

eBooks Year Month

1 1971 July

10 1991 January

100 1994 January

1000 1997 August

1500 1998 October

2000 1999 December

2500 2000 December

3000 2001 November

4000 2001 October/November

6000 2002 December*

9000 2003 November*

10000 2004 January*

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation has been created

to secure a future for Project Gutenberg into the next millennium.

We need your donations more than ever!

As of February, 2002, contributions are being solicited from people

and organizations in: Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, Connecticut,

Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois,

Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Massachusetts,

Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New

Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Ohio,

Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South

Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, West

Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

We have filed in all 50 states now, but these are the only ones

that have responded.

As the requirements for other states are met, additions to this list

will be made and fund raising will begin in the additional states.

Please feel free to ask to check the status of your state.

In answer to various questions we have received on this:

We are constantly working on finishing the paperwork to legally

request donations in all 50 states. If your state is not listed and

you would like to know if we have added it since the list you have,

just ask.

While we cannot solicit donations from people in states where we are

not yet registered, we know of no prohibition against accepting

donations from donors in these states who approach us with an offer to

donate.

International donations are accepted, but we don't know ANYTHING about

how to make them tax-deductible, or even if they CAN be made

deductible, and don't have the staff to handle it even if there are

ways.

Donations by check or money order may be sent to:

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

PMB 113

1739 University Ave.

Oxford, MS 38655-4109

Contact us if you want to arrange for a wire transfer or payment

method other than by check or money order.

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation has been approved by

the US Internal Revenue Service as a 501(c)(3) organization with EIN

[Employee Identification Number] 64-622154. Donations are

tax-deductible to the maximum extent permitted by law. As fund-raising

requirements for other states are met, additions to this list will be

made and fund-raising will begin in the additional states.

We need your donations more than ever!

You can get up to date donation information online at:

http://www.gutenberg.net/donation.html

***

If you can't reach Project Gutenberg,

you can always email directly to:

Michael S. Hart hart@pobox.com

Prof. Hart will answer or forward your message.

We would prefer to send you information by email.

**The Legal Small Print**

(Three Pages)

***START**THE SMALL PRINT!**FOR PUBLIC DOMAIN EBOOKS**START***

Why is this "Small Print!" statement here? You know: lawyers.

They tell us you might sue us if there is something wrong with

your copy of this eBook, even if you got it for free from

someone other than us, and even if what's wrong is not our

fault. So, among other things, this "Small Print!" statement

disclaims most of our liability to you. It also tells you how

you may distribute copies of this eBook if you want to.

*BEFORE!* YOU USE OR READ THIS EBOOK

By using or reading any part of this PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm

eBook, you indicate that you understand, agree to and accept

this "Small Print!" statement. If you do not, you can receive

a refund of the money (if any) you paid for this eBook by

sending a request within 30 days of receiving it to the person

you got it from. If you received this eBook on a physical

medium (such as a disk), you must return it with your request.

ABOUT PROJECT GUTENBERG-TM EBOOKS

This PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm eBook, like most PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm eBooks,

is a "public domain" work distributed by Professor Michael S. Hart

through the Project Gutenberg Association (the "Project").

Among other things, this means that no one owns a United States copyright

on or for this work, so the Project (and you!) can copy and

distribute it in the United States without permission and

without paying copyright royalties. Special rules, set forth

below, apply if you wish to copy and distribute this eBook

under the "PROJECT GUTENBERG" trademark.

Please do not use the "PROJECT GUTENBERG" trademark to market

any commercial products without permission.

To create these eBooks, the Project expends considerable

efforts to identify, transcribe and proofread public domain

works. Despite these efforts, the Project's eBooks and any

medium they may be on may contain "Defects". Among other

things, Defects may take the form of incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other

intellectual property infringement, a defective or damaged

disk or other eBook medium, a computer virus, or computer

codes that damage or cannot be read by your equipment.

LIMITED WARRANTY; DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES

But for the "Right of Replacement or Refund" described below,

[1] Michael Hart and the Foundation (and any other party you may

receive this eBook from as a PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm eBook) disclaims

all liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including

legal fees, and [2] YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE OR

UNDER STRICT LIABILITY, OR FOR BREACH OF WARRANTY OR CONTRACT,

INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE

OR INCIDENTAL DAMAGES, EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE

POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGES.

If you discover a Defect in this eBook within 90 days of

receiving it, you can receive a refund of the money (if any)

you paid for it by sending an explanatory note within that

time to the person you received it from. If you received it

on a physical medium, you must return it with your note, and

such person may choose to alternatively give you a replacement

copy. If you received it electronically, such person may

choose to alternatively give you a second opportunity to

receive it electronically.

THIS EBOOK IS OTHERWISE PROVIDED TO YOU "AS-IS". NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, ARE MADE TO YOU AS

TO THE EBOOK OR ANY MEDIUM IT MAY BE ON, INCLUDING BUT NOT

LIMITED TO WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A

PARTICULAR PURPOSE.

Some states do not allow disclaimers of implied warranties or

the exclusion or limitation of consequential damages, so the

above disclaimers and exclusions may not apply to you, and you

may have other legal rights.

INDEMNITY

You will indemnify and hold Michael Hart, the Foundation,

and its trustees and agents, and any volunteers associated

with the production and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm

texts harmless, from all liability, cost and expense, including

legal fees, that arise directly or indirectly from any of the

following that you do or cause: [1] distribution of this eBook,

[2] alteration, modification, or addition to the eBook,

or [3] any Defect.

DISTRIBUTION UNDER "PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm"

You may distribute copies of this eBook electronically, or by

disk, book or any other medium if you either delete this

"Small Print!" and all other references to Project Gutenberg,

or:

[1] Only give exact copies of it. Among other things, this

requires that you do not remove, alter or modify the

eBook or this "small print!" statement. You may however,

if you wish, distribute this eBook in machine readable

binary, compressed, mark-up, or proprietary form,

including any form resulting from conversion by word

processing or hypertext software, but only so long as

*EITHER*:

[*] The eBook, when displayed, is clearly readable, and

does *not* contain characters other than those

intended by the author of the work, although tilde

(~), asterisk (*) and underline (_) characters may

be used to convey punctuation intended by the

author, and additional characters may be used to

indicate hypertext links; OR

[*] The eBook may be readily converted by the reader at

no expense into plain ASCII, EBCDIC or equivalent

form by the program that displays the eBook (as is

the case, for instance, with most word processors);

OR

[*] You provide, or agree to also provide on request at

no additional cost, fee or expense, a copy of the

eBook in its original plain ASCII form (or in EBCDIC

or other equivalent proprietary form).

[2] Honor the eBook refund and replacement provisions of this

"Small Print!" statement.

[3] Pay a trademark license fee to the Foundation of 20% of the

gross profits you derive calculated using the method you

already use to calculate your applicable taxes. If you

don't derive profits, no royalty is due. Royalties are

payable to "Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation"

the 60 days following each date you prepare (or were

legally required to prepare) your annual (or equivalent

periodic) tax return. Please contact us beforehand to

let us know your plans and to work out the details.

WHAT IF YOU *WANT* TO SEND MONEY EVEN IF YOU DON'T HAVE TO?

Project Gutenberg is dedicated to increasing the number of

public domain and licensed works that can be freely distributed

in machine readable form.

The Project gratefully accepts contributions of money, time,

public domain materials, or royalty free copyright licenses.

Money should be paid to the:

"Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

If you are interested in contributing scanning equipment or

software or other items, please contact Michael Hart at:

hart@pobox.com

[Portions of this eBook's header and trailer may be reprinted only

when distributed free of all fees. Copyright (C) 2001, 2002 by

Michael S. Hart. Project Gutenberg is a TradeMark and may not be

used in any sales of Project Gutenberg eBooks or other materials be

they hardware or software or any other related product without

express permission.]

*END THE SMALL PRINT! FOR PUBLIC DOMAIN EBOOKS*Ver.02/11/02*END*